In the bustling Friday market of “Pul-e Pashtun” in Herat, among the noise of bargaining voices and the scent of dust and sweat, small cloth sacks wriggle faintly on the ground. Inside them are snakes — vipers, cobras, boas, and several other species — captured from the surrounding farmlands and brought here for sale. Over the past months, the trade in venomous and nonvenomous snakes has surged dramatically. But behind this growing market hides a quiet ecological disaster — one that is steadily disrupting the natural balance of life in Herat’s farmlands.

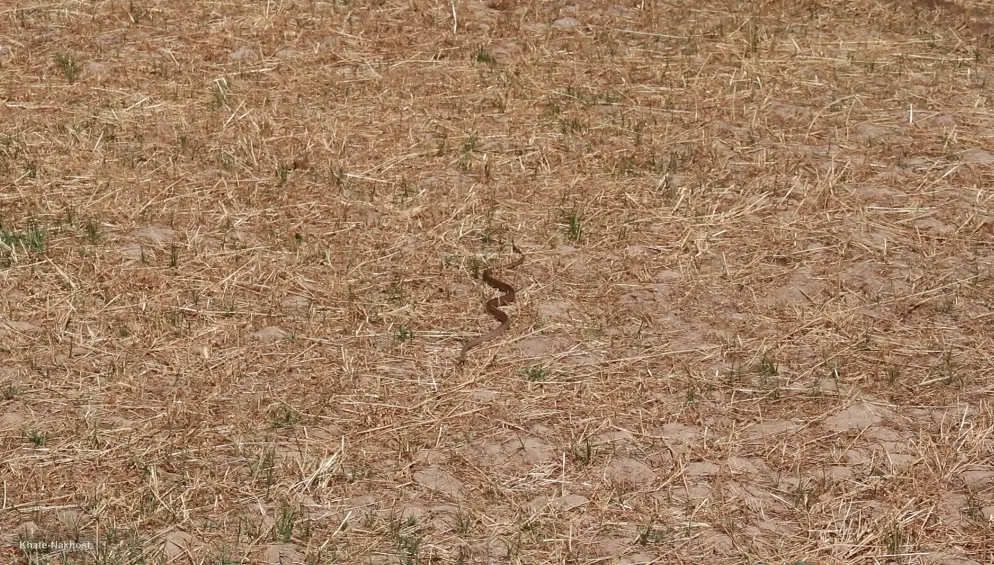

Noor Ahmad, a resident of Siyawushan village in Guzara district, has been catching snakes for more than seven years. He first encountered this trade at the Pul-e Pashtun market. What began as curiosity soon became both his livelihood and his greatest daily risk. “Catching snakes isn’t easy,” he says. “Three times I’ve been bitten by venomous snakes, but I survived. In the early days I used to carry antivenom from the pharmacy, but now I’ve learned how to handle them safely. The problem is, there aren’t as many snakes anymore. Three years ago, I could catch ten to fifteen in a week; now I’m lucky if I find five or six. The land doesn’t feel alive like before.”

Noor Ahmad admits that he knows the consequences of this work. “When the snakes are gone, the rats come,” he explains. “The soil becomes sick. But I have no other choice. There’s no work — and my children need bread.”

In the fields and dry plains of Herat, Noor Ahmad is not alone. Ghulam Nabi, a 35-year-old man from Injil district, has been hunting snakes for more than a decade. Every morning he rides his motorcycle up to thirty kilometers from home in search of snakes. “Three years ago,” he says, “I used to catch around forty a week. Now it’s ten, maybe fifteen. Even in Siyawushan, where the ground used to be full of snakes, you can wait for hours without seeing one.”

The decline in snake populations has had an immediate impact on farmers. As snakes disappear, rodents thrive. Abdul Samad, a 35-year-old farmer from Ziaratjah village in Guzara district, says: “When there were snakes, there were no rats. Now the fields are full of them. They dig up the seeds and chew the roots of the trees. At night, I can hear them running through the crops. We’ve started using chemical pesticides to fight them, but those chemicals are killing the soil. Either way, the land suffers.”

Across the world, environmental experts warn that snakes play a critical role in natural pest control. They are among the most effective regulators of rodent populations — and when they vanish, ecosystems collapse. Studies by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) show that over the past decade, nearly 20 percent of snake species across South Asia and the Middle East are now threatened with extinction. In countries like Iran, Pakistan, and India, illegal snake hunting — often for traditional medicine, leather, or display — has led to a dramatic loss of biodiversity.

In Afghanistan, the problem has taken on a silent form. With limited oversight and deepening poverty, local snake catchers see no alternative source of income. Some sell their catch to traders; others, like Hafiz from Herat city, keep snakes as exotic pets. “I’ve bought more than thirty snakes,” Hafiz says proudly. “I built a glass room in my house to keep them. When guests come, I show them off.” Most of the snakes he buys die within weeks — a personal hobby that mirrors a larger environmental tragedy.

According to Hamed Elham, Head of Communications at the Herat Directorate of Environmental Protection, snake hunting is entirely illegal. “There is no legal permission for snake catching in Herat,” he says. “Anyone involved in this activity will be arrested and punished under environmental law. We ask citizens to report any cases of snake hunting or trading.”

Experts warn that the disappearance of snakes will push farmers toward greater dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, degrading soil health and threatening food safety. “Snakes are silent protectors of agriculture,” says one environmental specialist. “Removing them is like taking a key stone from a wall — once it falls, everything else collapses.”

What is unfolding in Herat mirrors a global crisis: the human struggle between survival and sustainability. From the forests of the Amazon to the deserts of Balochistan, from Southeast Asia’s markets to the dusty plains of western Afghanistan, the pattern is the same — poverty, ignorance, and the absence of effective environmental governance.

If no urgent action is taken — to raise awareness, enforce environmental laws, and create alternative livelihoods for snake catchers — this silent imbalance could grow into an ecological and agricultural catastrophe. For centuries, snakes have been nature’s unseen guardians. Their disappearance is more than a loss of species; it is a warning — a whisper from the earth that its balance is breaking.