In a small village in western Afghanistan, a woman named Golbakht spends her days sitting behind a wooden loom. Her fingers move quickly, tying thousands of knots into a pattern she learned from her mother. Beside her, an 11-year-old girl—her daughter—works quietly, following her lead.

It takes nine months to finish a single carpet. When it’s done, Golbakht earns about 9,000 afghanis (around $150) — barely enough to survive. Her husband is unemployed, her 12-year-old son is disabled, and some days there’s no meat on the family’s table. Yet she keeps weaving.

“We have no other choice,” she says. “This is the only way to stay alive.”

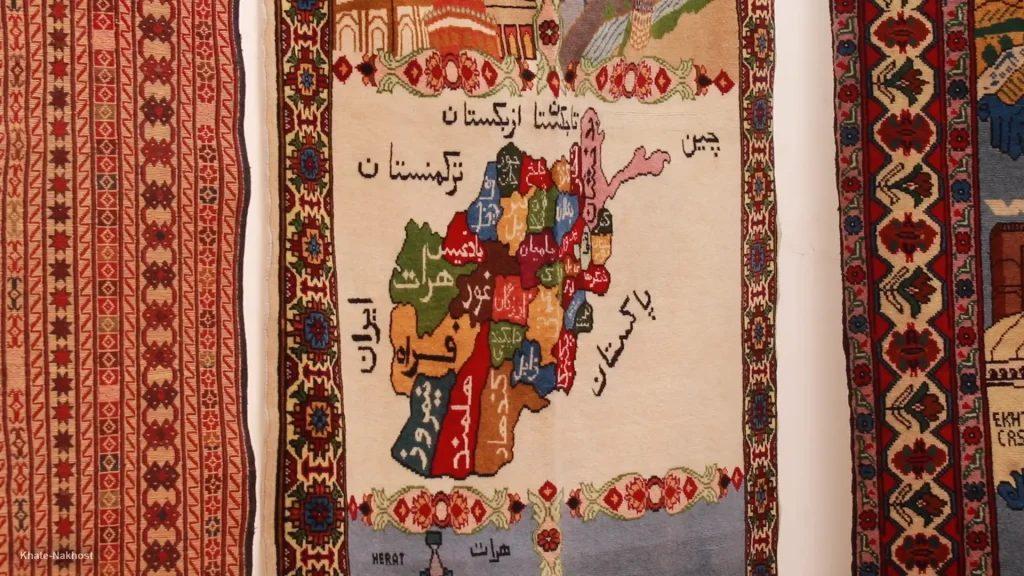

Golbakht’s story mirrors that of thousands of women in Herat and other western provinces who carry on Afghanistan’s centuries-old carpet weaving tradition — an art admired worldwide for its quality but struggling to survive amid poverty, outdated designs, and shrinking markets.

Now, a new initiative in Herat aims to change that.

For the first time in Afghanistan, Herat University has launched a Department of Carpet Design within its Faculty of Fine Arts. The program seeks to combine traditional craftsmanship with modern design and marketing techniques, helping revive one of the country’s most iconic industries.

Abdul Tawfiq Rahmani, Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts, told khate-nakhost:

“We are admitting students to this new department through the 1404 university entrance exam. It’s the first academic program in the country focused entirely on carpet design.”

According to Rahmani, four instructors have been hired to teach courses in design, weaving, marketing, and trade. The department will accept up to 80 students from across Afghanistan. Its facilities have been equipped by the Ministry of Higher Education, with additional support from TIKA, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency.

He added that the department aims to operate at a standard comparable to institutions in Iran and Turkey, and that some of its instructors have 30 to 40 years of professional experience in traditional carpet weaving.

Graduates, Rahmani hopes, will find opportunities in both local and international carpet industries.

Meanwhile, Mohammad Rasool Fayeq, administrative manager of the Carpet Exporters’ Union in western Afghanistan, believes marketing remains the key challenge.

“Production continues in traditional ways, but the buyers are no longer there as they once were,” he said. “We need innovation to bring Afghan carpets back to the global market.”

Fayeq estimates that 30 to 35 percent of Afghanistan’s carpets are produced in the country’s western provinces, where around 350,000 looms are still active. He lists India, Turkey, and China as major competitors but insists that Afghan carpets remain unmatched in quality and authenticity.

Back in Zindajan district, Golbakht continues her work, knot by knot, her hands rough but steady. Each thread she ties holds not just color and wool—but the weight of survival, hope, and tradition.

Experts say that initiatives like Herat University’s new department could help transform stories like hers—from one of struggle to one of opportunity—preserving Afghanistan’s cultural heritage while empowering the women who keep it alive.

1 comment

Your work is amazing!