In the western Afghan city of Herat — a historic center of art and architecture that once flourished under the Timurid Empire — the ancient craft of pottery still struggles to survive.

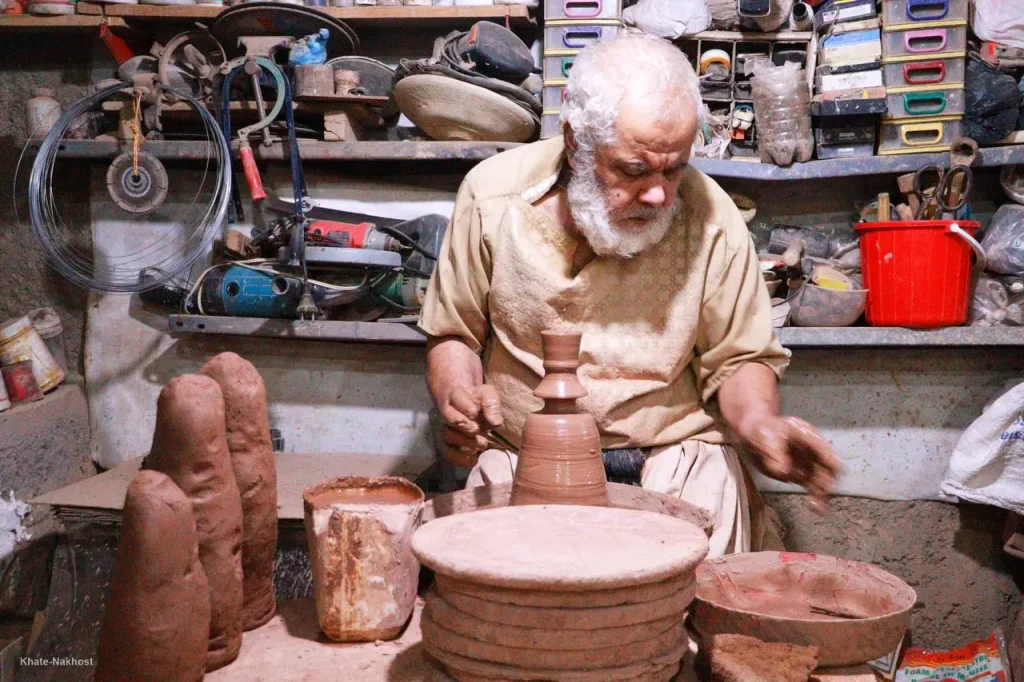

In a quiet, dimly lit basement workshop, two potters sit at their wheels, their hands moving with a rhythm shaped by decades of practice. The scent of damp clay mixes with the sound of spinning wood — a song of patience and persistence. Here, Hakmatullah Ghulami, the workshop’s supervisor, carefully shapes a new clay pot.

Hakmatullah has over twenty years of experience in producing pottery and ceramic items, which is his main source of livelihood. He explains that the pottery industry in Herat is in decline: of the seventy-two types of pottery once produced, today only four or five remain. Production has dropped to a minimum, and despite decades of dedication, the craft no longer thrives. In recent years, closures of supporting institutions and restrictions on women’s activities have further weakened the industry.

Currently, they mostly produce small items, some of which are exported to Iran at low prices. Sorkhuneh — traditional clay bowls used for tobacco pipes — is one of the few items sent abroad.

Approximately a month ago, Hakmatullah met with the Governor of Herat to highlight these challenges and request support. He warns that without assistance, this centuries-old craft may disappear entirely, as few experienced Afghan potters remain in the city.

In the same workshop, an elderly yet skilled craftsman, Ghulam Jilan, aged 65, continues to work. He began learning pottery at the age of six, attending the mosque in the mornings and the workshop in the afternoons.

Reflecting on the past, Ghulam Jilan recalls: “Thirty years ago, the pottery trade was thriving. Customers would wait in line, and multiple artisans worked in each workshop, each specializing in a specific task. There were over fourteen active workshops in Herat, and the market was bustling.”

Twenty years ago, he and his five brothers made pottery for local flower vendors. Today, many of those customers have passed away, and potters have been forced to change professions due to the lack of a market.

Ghulam Jilan produces around 100 small pottery items daily, earning only one Afghan afghani per piece — approximately one and a half U.S. dollars in total, half of which goes toward commuting between home and workshop. Despite having the skills to teach and train new potters, he and his colleagues receive no support to help revive their craft.

For centuries, pottery has been part of Afghan daily life — from household vessels to decorative art — reflecting both utility and cultural beauty. Yet today, this timeless art faces an uncertain future. The influx of plastic, glass, and metal goods, combined with limited institutional support, has pushed Afghanistan’s traditional pottery to the brink of extinction.

In Herat’s fading workshops, the hum of the potter’s wheel still echoes — a reminder that Afghanistan’s cultural soul endures, even in silence.

- Herat University Launches Carpet Design Department: A Step Toward Bridging Tradition and Modern Education

- Tourism Week Celebrated at the Ikhtiyaruddin Citadel in Herat

- Herat’s Tazhib (Islamic Illumination) & Miniature Art: Preserving Afghanistan’s Timeless Heritage

- Afghan Women Revive Herat’s Miniature Art, UNESCO-Recognized Tradition